INSTALLATION LOG // >

Exhibit Entry Twenty-Two Distortion Dialogue

“To Gaza, all this poetic language is dedicated.”

What does it mean to be a fine artist in a place that won’t even let you be whole?

For Bayan Abu Nahla, a visual artist from Gaza, it means working with grief as medium. It means pigment as protest. It means creating images that speak, when the rest of the world refuses to listen.

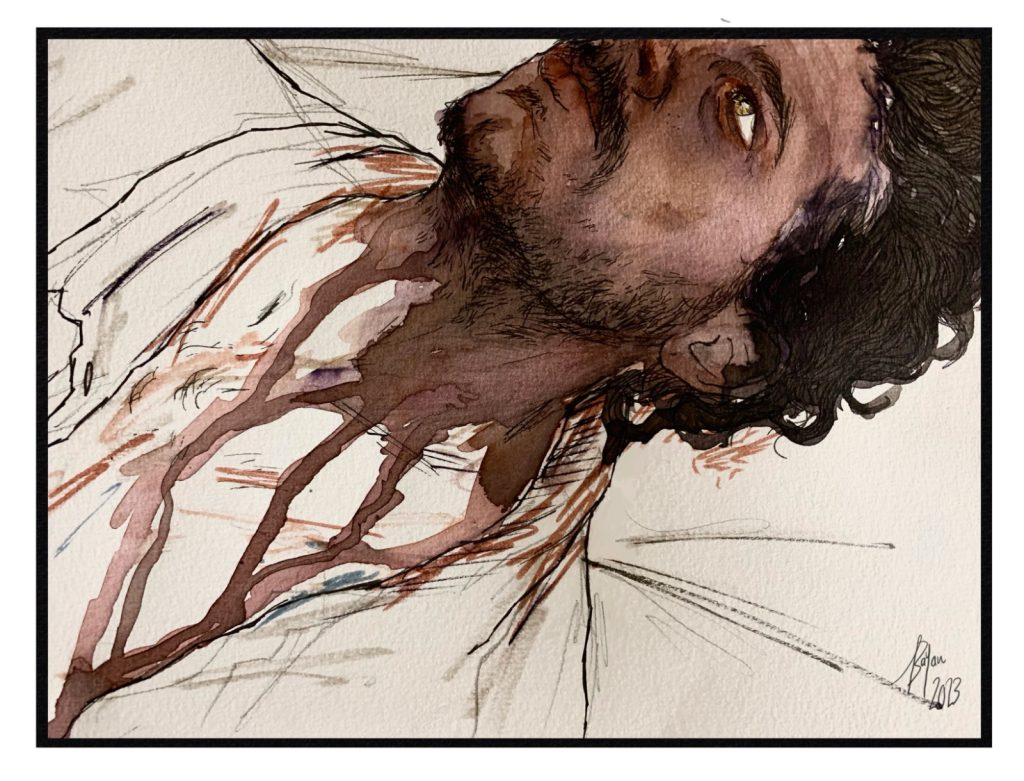

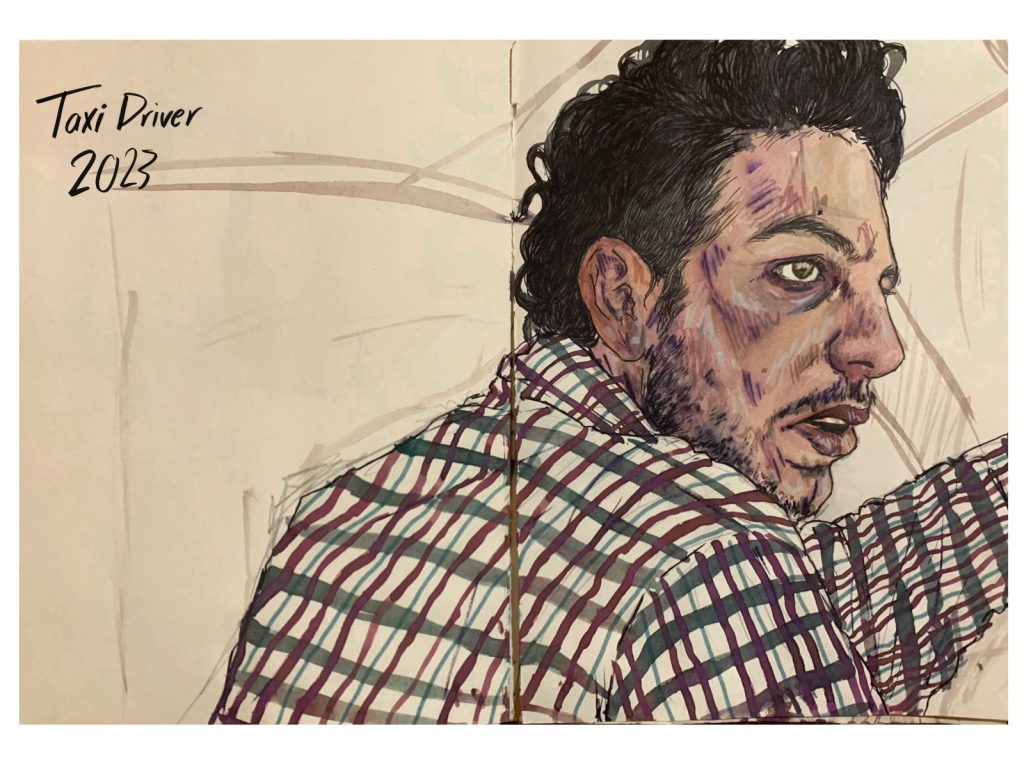

Born and raised in the Gaza Strip, Bayan paints and draws the story of her people—not through bombs and flags, but through faces. Expressions. Memory. Her work is rooted in a tradition as old as resistance itself: the act of drawing a life not to make it pretty, but to prove it existed. As she puts it:

“My art is melancholic, sorrowful, pointed… It takes on the function of art in catharsis by expressing the despondency planted within us by a cruel life.”

Her portraits do not sensationalize pain. They sit with it. Often rendered in ink and watercolor, her figures appear suspended in quiet reflection—eyes turned away, gazes vacant, hands clenched or limp. These are not violent images, but they are not soft either. They’re emotionally charged, exacting in their intimacy. You can see the weight carried in each expression, the tenderness layered under fatigue. There’s no need for captions—you feel it in the curl of a lip, the posture of a head.

Her work is deeply human—and deliberately specific.

These are not “universal” representations of suffering. They are Gazan. Palestinian. Her figures are almost always anonymous, but not faceless. Each portrait becomes a placeholder for someone you didn’t know you lost. Or someone you were never allowed to grieve.

There’s a warmth to her palette—rust, earth tones, dusty mauves, deep shadows—that offsets the emotional coolness of the figures. She often avoids overt political imagery. No flags. No missiles. Just the after. Just the ache.

In one portrait, a woman’s eyes are half-lidded, her shoulders slightly hunched as though caught in the moment after screaming, or just before. In another, a child’s head rests on an adult’s lap, the two of them rendered in shades of red so subtle you almost miss the blood. The subtlety is the point. This is not art made to shock—it’s made to last.

Abu Nahla’s work is part catharsis, part archive. Like many artists who have lived through war—think Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz, Charlotte Salomon—she documents atrocity not from afar, but from within. But unlike those artists, Bayan does not draw from memory in the safety of post-war exile. She is still inside it. The bombs haven’t stopped. The siege has not lifted.

She is still alive.

And like fellow Gazan voices such as Bisan Owda, who repeats “I’m still alive” in her video updates as both affirmation and challenge, Bayan paints with the same intent: to mark presence. To scream, softly, through ink: we are here.

“My art takes after my life, or how I feel about my life. To Gaza, all this poetic language is dedicated.”

This is what it means to be a Palestinian artist under occupation. You are not granted the luxury of introspection without context. Every stroke is political. Every exhibition is a demand. Every drawing is interrupted by the sound of drones.

Art created under siege is not an escape—it’s a pulse check.

There is a long tradition of artists making work in impossible conditions. Charlotte Salomon painted her life story while hiding from the Nazis. Etel Adnan wrote poetry of exile from Lebanon. Artists in Sarajevo sketched scenes between sniper fire. Bayan joins this lineage—not in a gallery, but on the floor of her home, her window rattling with airstrikes.

There is no studio. Just paper. Just feeling. Just truth.

In a world that often demands Palestinians prove their humanity before receiving empathy, Bayan refuses the performance. She doesn’t ask for permission to feel. She doesn’t draw to soften the reality. She draws to show it.

Because that’s what art does.

It holds what the news cycle drops.

It remembers what the rubble buries.

It makes visible what war tries to erase.

So if you want to understand Gaza—really understand it—start here.

Not with statistics.

Not with soundbites.

But with the eyes of a mother in watercolor.

The shadowed brow of a boy in ink.

The trembling hands of an artist, still sketching.

Still surviving.

Still resisting.

Still alive.

Prompt+Original

Edit 1

Edit 2

Feed the Paws…

💜 Help keep the chaos caffeinated and the cats in biscuits. Every crumb helps. Whether you’re funding feline existential monologues, glitchy portals, or late-night creativity spirals, your support feeds the moglets (and occasionally, the magic). 🐈⬛

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Thank you, fellow wanderer. Your generosity has been noted in the Book of Kindness, which the cats may or may not use as a pillow.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyDiscover more from River and Celia Underland

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.