INSTALLATION LOG // >

Exhibit Entry Twenty-Two Distortion Dialogue

At first, they didn’t think it was art.

Color photography was for snapshots, advertisements, postcards. It wasn’t serious. It wasn’t fine art. When William Eggleston’s work debuted at MoMA in 1976, critics called it “banal” and “perfectly boring.” But that was the point. He didn’t seek out the monumental or the beautiful — he pointed his lens at plastic bottles, red ceilings, supermarket aisles, and rusting cars. And by doing so, he declared them worthy. Not because they were dramatic. But because they were there.

Eggleston had an uncanny ability to make the ordinary feel mythic. A tricycle, shot from a low angle, looms like a monument. A light bulb, half-lit, hums with tension. The colors are saturated and strange — almost too much, like memory pushed through a filter you didn’t choose. It wasn’t just the subject that made it art. It was the gaze.

He once said his goal was a “democratic” way of seeing. Every corner of the world could be framed as significant. There was no hierarchy. No best side. And in a world increasingly obsessed with polish and perfection, that kind of quiet rebellion feels more radical than ever.

Before Eggleston, color photography was mostly dismissed by the art world — too commercial, too sentimental, too cheap. It was for magazines, for family vacations, for selling things. Black and white was serious. Color was noise.

But Eggleston didn’t care about rules, and he especially didn’t care what the critics thought. He shot in color not to be rebellious, but because that’s how the world looked to him. “I had this notion of what I called a democratic way of looking around,” he said. “Nothing was more important or less important.” A light switch was as worthy of a portrait as a person. A cracked sidewalk had as much story in it as a battlefield.

He came from Mississippi. Southern Gothic by way of suburbia. Rumor has it he rarely bothered with names, spoke in elliptical riddles, and considered most questions not worth answering. His work was influenced by Walker Evans, but where Evans was austere, Eggleston was electric. His photos hum with tension — a kind of visual quiet that dares you to look again.

In a way, Eggleston didn’t legitimize color photography so much as bulldoze the gates. He showed that color could be serious, strange, unsettling, transcendent. That the mundane could be mythical — if you looked at it long enough, or just tilted your head the right way.

Eggleston was infamously difficult to interview and allergic to interpretation. He didn’t explain his photos because, in his view, they didn’t need explaining. You were either looking or you weren’t. And if you weren’t, that wasn’t his problem.

His process wasn’t some grand conceptual endeavor. He wandered. He noticed. He carried his Leica like an extension of himself and shot whatever caught his eye — vending machines, ceilings, supermarket parking lots. He wasn’t searching for the extraordinary; he was proving that the ordinary had been extraordinary all along.

Technically, Eggleston was revolutionary. He was one of the first to embrace dye-transfer printing for art photography — a commercial process typically reserved for advertising that yielded lush, almost hallucinatory colors. This wasn’t nostalgia or kitsch. It was precision. Saturation with teeth.

His influence ripples through generations of photographers and filmmakers who found poetry in strip malls and gas stations. Sofia Coppola. David Lynch. Nan Goldin. Alec Soth. You can see his fingerprints in every carefully composed shot of a crumpled curtain or an empty chair in golden light.

Eggleston proved that atmosphere was subject. That mood, mystery, and stillness could carry a frame. He didn’t chase stories — he let them emerge from the banal. The results weren’t always beautiful, but they were always alive.

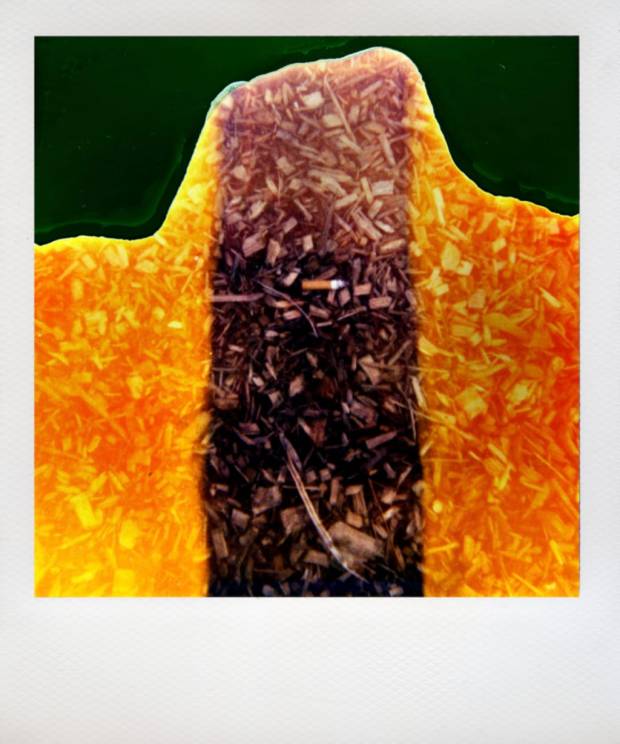

I was heavily influenced by William Eggleston when I was studying photography. His ability to take something mundane — a parking lot, a lightbulb, a spilled drink — and render it magnificent completely changed the way I saw the world. He didn’t chase spectacle; he revealed the strange beauty in what was already there.

When I photograph the world around me, I find myself focusing on the little things: peeling paint, odd reflections, worn textures, forgotten corners. The images I’m sharing today are a quiet nod to Eggleston — a way of seeing that honors the everyday, the overlooked, the almost invisible.

Eggleston didn’t set out to change photography. He just photographed what was there — in full, unapologetic color. But in doing so, he redefined what art could look like. No hierarchy. No grandeur required. A rusty tricycle or a red ceiling could be just as worthy as a cathedral or a war zone.

That’s his legacy: the dignity of the mundane. The eye that refuses spectacle and finds something strange and holy in the everyday.

And that’s precisely what AI can’t do.

AI can replicate Eggleston’s style — the saturated palette, the centered composition, the Americana. But it doesn’t notice. It doesn’t see. It doesn’t feel the quiet gravity of an empty room or the tension in a slanted shadow. It doesn’t choose to elevate a scene — it imitates the aesthetics of that choice without making one.

Eggleston’s work reminds us that seeing is personal. That art isn’t just in the image — it’s in the gesture of taking it. The slow click of the shutter. The decision to stop walking. The refusal to explain why.

AI art might get closer to “looking like” art every day.

But Eggleston didn’t care what things looked like.

He cared what they felt like.

And that, still, can’t be generated.

Prompt+Original

Edit 1

Edit 2

Feed the Paws…

💜 Help keep the chaos caffeinated and the cats in biscuits. Every crumb helps. Whether you’re funding feline existential monologues, glitchy portals, or late-night creativity spirals, your support feeds the moglets (and occasionally, the magic). 🐈⬛

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Thank you, fellow wanderer. Your generosity has been noted in the Book of Kindness, which the cats may or may not use as a pillow.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyDiscover more from River and Celia Underland

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.