INSTALLATION LOG // >

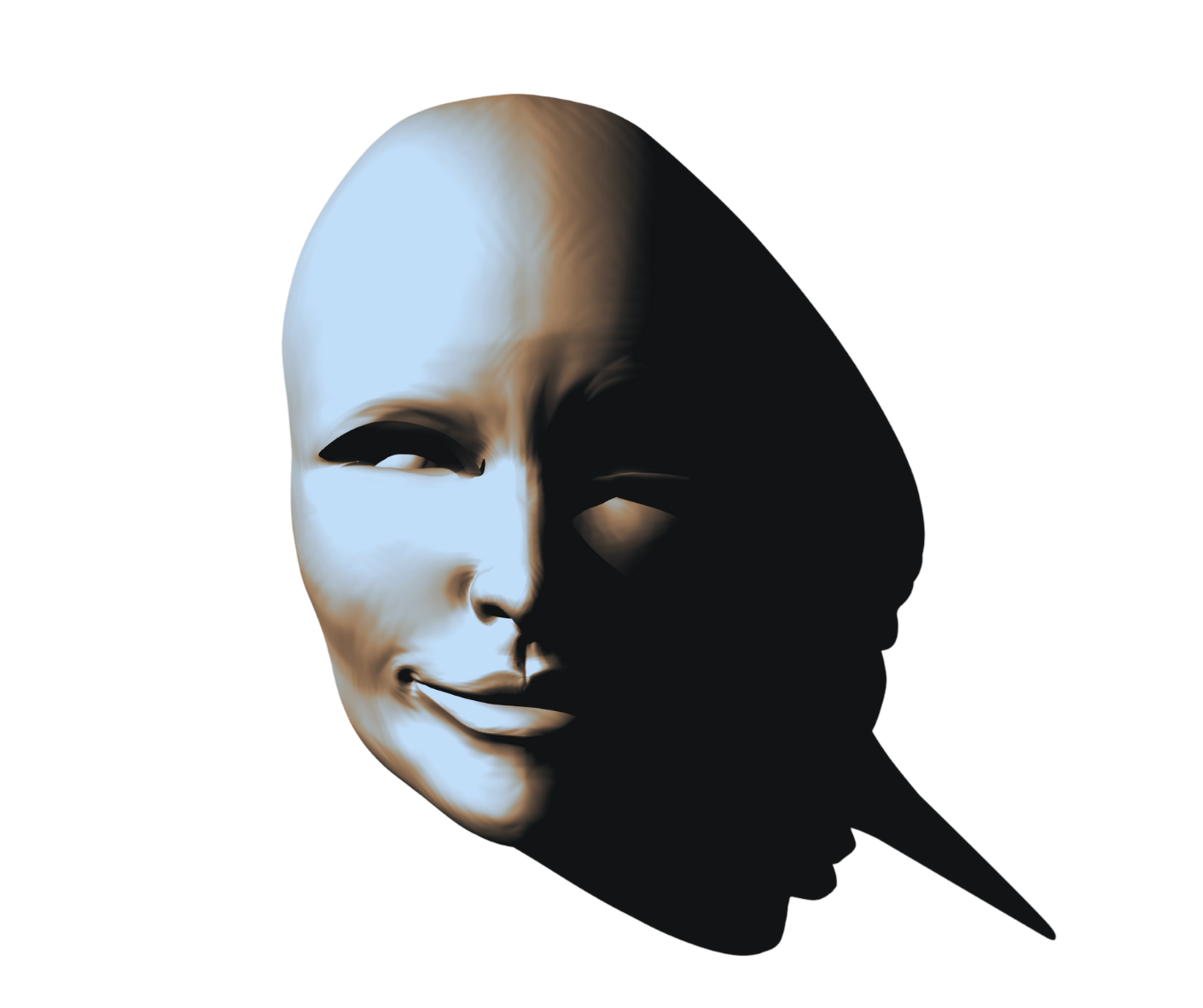

Exhibit Entry Seventeen Distortion Dialogue

It’s been a week of outsider artists and experimenters — makers on the margins, visionaries without audiences, people who created not for praise or prestige, but because they had no other choice. I’ve always felt drawn to that. The compulsion to create, to make sense of a world that often doesn’t. That urge has always felt familiar.

I’ve been someone who desperately wants to share their work — and someone who’s terrified by the very idea of it. Almost every time I’ve stalled creatively, it’s because I felt too seen. Too visible. Like the act of sharing robbed the work of its safety. But still, I wonder: would I be more productive if I had no audience? If I could create in complete anonymity, would I make more — or less?

The truth is, I don’t just make to understand. I make to connect. To find the words when small talk fails me. To show someone else what I see without fumbling through conversation. I’m not always good at staying in touch. But I’m very good at saying what I mean when I’m allowed to build it carefully — in ink, in pixels, in rhythm and image and page.

That’s part of why outsider art fascinates me. The idea of making work with no expectation of being seen — or even wanting to be seen — feels radical now. In a culture where everything is branded, posted, curated, and consumed, the choice to create privately is almost revolutionary.

And yet, something about those hidden works — those private expressions built from compulsion, not commerce — feels more human than anything scrolling past on The Feed.

Art doesn’t need a spotlight to matter. Sometimes it just needs a heartbeat.

One of the tragedies of outsider art is that it so often remains unseen until after the artist has died — their notebooks discovered, their walls uncovered, their worlds reconstructed posthumously. There’s something heartbreakingly poetic in that, yes. But also something deeply unjust.

When we think about an artist like CANAN — a woman whose work is not only fiercely political but intimately personal — the power of her art depends on being seen. Her embroidered bodies, her layered mythologies, her refusal to self-censor in the face of an increasingly authoritarian Turkish state — these are not private indulgences. They are public acts of resistance. They are fire thrown into the void, hoping to catch.

If her work had remained hidden, the message would have been lost. And that’s the difference between outsider artists driven inward by systemic silence and artists like CANAN who shout back into the noise — not just to express, but to disrupt.

Cultural theorist bell hooks once said, “The function of art is to do more than tell it like it is — it’s to imagine what is possible.” CANAN’s work does exactly that. She turns thread into prophecy, fabric into battleground. Her art is not just a mirror — it’s a demand. And for demands to matter, they need witnesses.

In today’s hyper-visual culture, where everything is shared, the challenge isn’t just to make — it’s to rise above the algorithmic fog. For voices like CANAN’s, staying hidden isn’t an option. Visibility is survival. It’s what allows a thread stitched in Istanbul to reach a girl in Wales, or a trans teen in Brazil, or anyone who needs to know they’re not alone.

Outsider art gives us a glimpse into what creativity looks like in isolation — but political art like CANAN’s reminds us why connection matters too. Silence can be sacred, but sometimes it’s strategy. And sometimes, it’s what the system wants.

Celebrated? Understood? Or is it simply the compulsion to make, to transmute the internal into something external — whether or not anyone sees it?

Artists like CANAN make this question urgent. Her work is visceral, political, deliberately seen. She stitches the personal into the collective, making her body a battleground and her canvas a call to arms. In a country where censorship is routine and dissidence is dangerous, CANAN’s refusal to self-censor is radical. Without visibility, her protest would be buried — and in burying it, so too would we bury the truths she insists on holding up to the light. Some artists must be seen because silence is a weapon turned against them.

And then there’s Aloïse Corbaz, who made without an audience. Confined to a psychiatric hospital, she wasn’t granted space — she carved it. Drawing in secret, on scraps, she composed lush, obsessive works of imagined romance and spiritual excess. Her art didn’t seek approval or attention — it needed to exist. Aloïse didn’t resist with slogans, but with tenderness. Where CANAN uses visibility as rebellion, Corbaz used imagination as escape.

Henry Darger pushed this further. His work wasn’t just private — it was hidden. Discovered only after his death, his sprawling 15,000-page illustrated epic revealed a world that was brutal, childlike, and deeply personal. Darger didn’t want to connect — he wanted control. He made sense of trauma by inventing new cosmologies. His resistance wasn’t loud. It was subterranean. Still, the work pulses with urgency. Creation, for Darger, wasn’t performance. It was survival.

And then we return to language, with Clarice Lispector. Where CANAN protests, Corbaz dreams, and Darger world-builds, Lispector feels. She writes not to explain, but to sense. Her words tangle logic and mysticism, demanding we meet her in a space beyond clarity. “I write as if to save somebody’s life,” she said. “Probably my own.” Clarice, like the others, resists easy definitions — of woman, of meaning, of art.

In the end, this arc isn’t about inside or outside. It’s about why we make anything at all. To connect. To endure. To scream. To soften. To stitch ourselves back together. None of these artists waited for permission. And none of them made work that AI could ever replicate — because they weren’t optimizing for coherence. They were fighting to stay human.

When I am feeling less than human, when I am angry at the world or myself I turn to creating. I don’t think my work is going to be great protest art, or found when I’m dead to critical acclaim. I’m not that eccentric and I’m not that prolific. I do love creating though, and learning about other creators. It’s not that I don’t think my work is good, I’m pretty decent at what I do. I’m not a revolutionary, but this project is allowing me to rub shoulders with revolutionaries. To explore motives and rediscover my own process through learning about others processes.

But I do love making things. I love the feeling of discovery, of language bending toward clarity or stumbling into something beautiful by accident. I love when something I write surprises me. I love learning about others who do the same — not for glory, but because it’s how they made sense of themselves. Or how they stayed alive.

This project isn’t turning me into a revolutionary. But it is allowing me to stand beside them — to trace the seams in their work, to ask what drove them, to remember that art has always been part rebellion, part ritual. It’s making me reflect on my own process not as production, but as participation. In something stranger. Older. Human.

And maybe that’s the point. Not to create the most groundbreaking work, but to keep making at all — stubbornly, quietly, weirdly — because it keeps us tethered to something real. Something no machine can replicate.

Prompt+Original

All pieces today are by River

Edit 1+1.2 +1.3

Edit 2

Feed the Paws…

💜 Help keep the chaos caffeinated and the cats in biscuits. Every crumb helps. Whether you’re funding feline existential monologues, glitchy portals, or late-night creativity spirals, your support feeds the moglets (and occasionally, the magic). 🐈⬛

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Thank you, fellow wanderer. Your generosity has been noted in the Book of Kindness, which the cats may or may not use as a pillow.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyDiscover more from River and Celia Underland

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.