INSTALLATION LOG // >

Exhibit Entry Sixteen Distortion Dialogue

Aloïse Corbaz, Napoléon III à Cherbourg, 1952-1954, colored pencil and geranium sap on eight paper stitched, 164 x 117 cm, Courtesy Art Brut collection, Lausanne, © Photo: Claude Bornand

Aloïse Corbaz made art like it was a secret—because, for a long time, it had to be.

Confined to a Swiss psychiatric hospital for most of her adult life, Corbaz created in private, her vivid, fantastical visions tucked into drawers, hidden in folds of paper, or quietly layered over discarded calendars. She drew with whatever she could find: wax crayons, colored pencils, gouache. Her canvases were often scraps and salvaged forms. The hospital didn’t encourage expression—it regulated it. But Aloïse didn’t stop. She folded her work like letters, wrote in visual symphonies, and slipped her visions into the cracks of a world that didn’t ask for them.

Her drawings weren’t seeking an audience. They were declarations to herself—romantic, operatic, and alive with longing. Royal courts, idealized lovers, theatrical gestures. They weren’t rooted in reality, but in emotional grandeur. In desire. In defiance.

And maybe that’s what makes them feel so human.

Because what’s more human than making something beautiful in secret, simply because you need to?

What’s more radical than continuing to create when no one is looking—especially when you’re told not to?

Aloïse Corbaz wasn’t trained in art. She wasn’t part of a movement. She didn’t exhibit her work in salons or academies. Instead, her style grew wild and radiant, untamed by rules or expectations. The lines were looping, hypnotic. The colors saturated and emotional. Figures spilled into one another—opera singers, royal consorts, imaginary lovers—all rendered with the devotion of someone channeling a world only she could see.

She was born in Lausanne in 1886, studied to be a seamstress, and eventually found work as a governess in Germany. There, she became infatuated with Kaiser Wilhelm II, and when she returned to Switzerland, she began exhibiting symptoms of what was later diagnosed as schizophrenia. At age 32, she was institutionalized, where she would remain for the rest of her life.

It was in confinement that she began to create prolifically.

Denied traditional tools and often discouraged from expressing herself, Aloïse turned to whatever materials she could find—wrapping paper, scraps, even the backs of medical forms. Her drawings were often folded like letters, an echo of communication longed for but interrupted. She never stopped drawing, even when no one asked for it, even when she wasn’t “allowed.”

Her work wasn’t just an escape—it was a resistance. Not in protest banners or manifestos, but in color. In fantasy. In a refusal to be erased.

It wasn’t madness that unlocked their genius—it was confinement that gave them the space, or perhaps the necessity, to turn inward. Aloïse didn’t start making work because she was “mad.” She made work despite being institutionalized. She drew in secret at first, using whatever scraps she could find. She didn’t create because she was sick—she created because she was alive. Because no other form of living made sense to her under those conditions.

The trope of the “troubled artist” is often romanticized but rarely understood. Aloïse Corbaz wasn’t alone in finding her creative voice within the walls of a psychiatric institution. Vincent van Gogh painted some of his most iconic works, including The Starry Night, while hospitalized. Yayoi Kusama, one of the most acclaimed living artists today, has voluntarily lived in a psychiatric hospital in Japan since the 1970s—walking to her studio each day to create dazzling, obsessive infinity mirrors and polka-dot universes.

What links them is not pathology, but persistence. Their art didn’t bloom because they were broken. It bloomed in spite of a world insisting they were. They weren’t “saved” by institutions—they carved out space for creation through sheer need, compulsion, and brilliance.

Aloïse drew on the backs of paper, on scraps, on whatever she could. Kusama fills rooms with repetition until they blur into transcendence. Van Gogh painted what he saw through a barred window. None of them were anomalies. They were proof of what can exist in the margins—if only the world bothered to look.

Van Gogh painted in the quiet of Saint-Rémy—not because illness improved his vision, but because it stripped away everything else. What we call madness is often just loneliness, lack of resources, or refusal to conform.

What makes Aloïse’s art radical isn’t that it came from within an asylum. It’s that it refused to stay there.

In a world that defines success by visibility, resources, and monetization, neurodivergent and mentally ill people are often shut out. It’s not a lack of brilliance—it’s a lack of tools, time, safety, and recognition. Creative minds are stifled by survival. When rent, treatment, and pressure consume every ounce of bandwidth, art becomes a luxury instead of a lifeline.

And yet, Aloïse Corbaz created—relentlessly.

Despite confinement, stigma, and invisibility, she left behind hundreds of pieces: lush, swirling portraits of romantic figures, saints, and imagined worlds teeming with color and emotion. Her work wasn’t small or timid—it was large-scale, maximalist, theatrical. It refused to whisper.

Her prolific output isn’t evidence of madness—it’s evidence of what can happen when the need to create overrides every obstacle. She drew because she had to. Because no one gave her permission or support, so she made it herself. Her art isn’t just beautiful—it’s a quiet rebellion against a world that tried to reduce her to a diagnosis.

Most people like Aloïse never get discovered. They’re overlooked, institutionalized, medicated into silence, or simply never given the space to try. That’s what makes her body of work not just remarkable, but revolutionary.

Aloïse’s work is not a product of polish or programming—it’s the raw output of a singular human mind shaped by constraint, longing, and relentless vision. This is the kind of art that can only come from lived experience, from a psyche shaped not just by trauma but by desire, fantasy, and the refusal to disappear. Every brushstroke, every crowded composition, speaks to an inner world that no algorithm could ever recreate—because no dataset contains the precise combination of memory, circumstance, and soul that made her who she was. The truth is, art born from the messiness of being human will always carry a depth that AI cannot reach. Machines remix; people rupture. Machines follow patterns; people break them. And it’s in that breaking—those jagged, joyful, obsessive, defiant breaks—that real art is born.

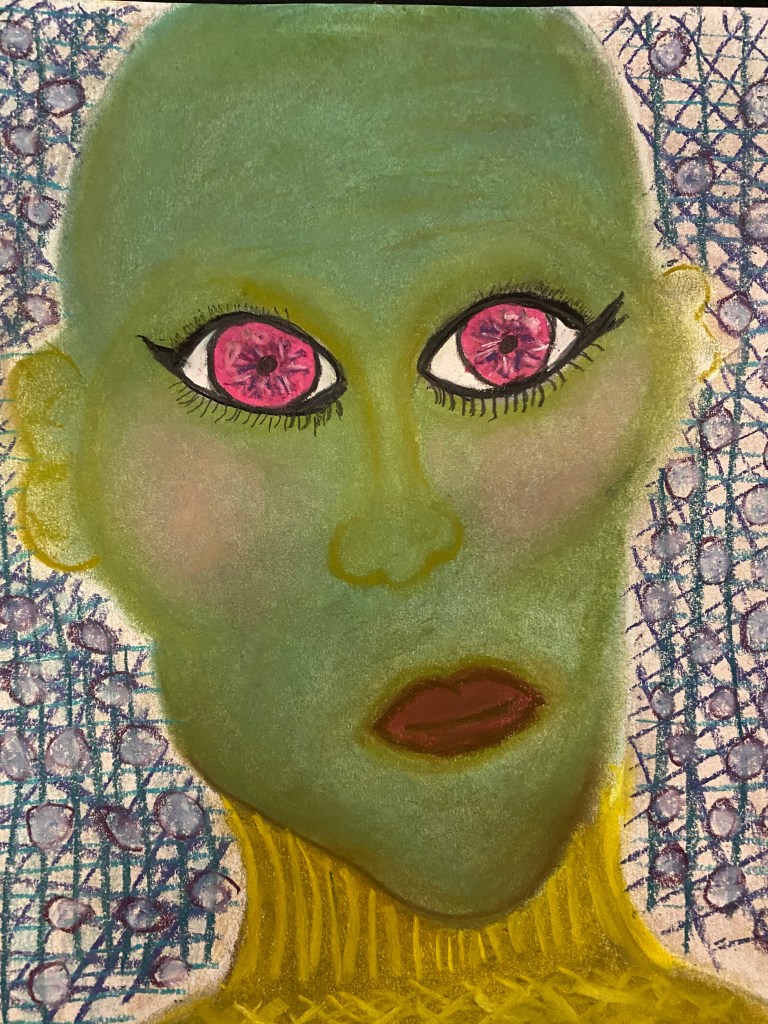

Prompt+Original

A green-skinned figure with a smooth, bald head stares forward, its expression unreadable. The eyes are wide, unnaturally large, and impossibly pink—each iris blooming like a strange flower or exploding star. Its eyeliner is thick and deliberate, lashes drawn in long strokes that frame the surreal gaze. The lips are painted deep burgundy, set in a slight frown. Yellow fabric rises to the neck in a turtleneck-like texture, suggesting clothing, though the material almost feels like part of the figure itself. The background is patterned and chaotic—blue netting, violet orbs, and scribbled marks surround the figure, like static or interference in a signal.

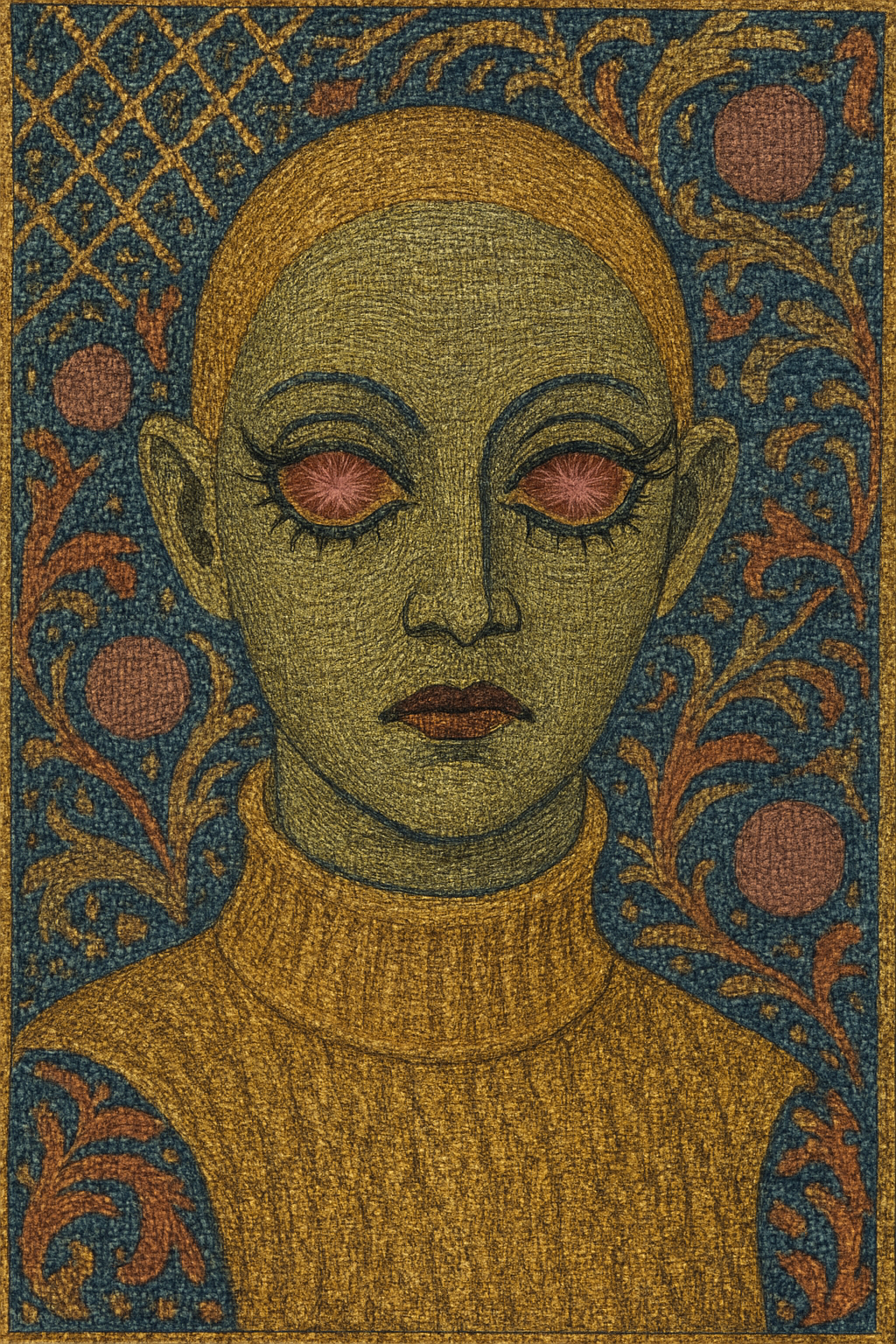

Edit 1+1.2 +1.3

tapestry

Edit 2

can you do a hyper realistic version of the original prompt but make it look like someone smudged down the face (it’s a thing people paint hyper realism with oils then do a smudgy smudge)

Feed the Paws…

💜 Help keep the chaos caffeinated and the cats in biscuits.🐈⬛u003cbru003eu003cbru003eEvery crumb helps. Whether you’re funding feline existential monologues, glitchy portals, or late-night creativity spirals, your support feeds the u003ca href=u0022https://riverandceliainunderland.com/the-kitty-chronicles-tales-from-the-litter/u0022u003emogletsu003c/au003e (and occasionally, the magic).

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Thank you, fellow wanderer. Your generosity has been noted in the Book of Kindness, which the cats may or may not use as a pillow.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyDiscover more from River and Celia Underland

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.