INSTALLATION LOG // >

Exhibit Entry Fourteen Distortion Dialogue

“Here I am with it still unsolved, & I seem to be losing my hold on life.”

Madge Gill

Madge Gill

Madge Gill didn’t set out to be an artist. She said she was guided.

There’s a kind of creativity that doesn’t chase attention. It doesn’t seek galleries, grants, or applause. It simply insists on existing. For Madge Gill, art was something she returned to over and over — not to be seen, but to be made.

After personal tragedies — the loss of her daughter, years of illness, and time in institutions — Gill began producing thousands of detailed ink drawings. She claimed to be working under the influence of “Myrninerest,” a spirit guide she never fully explained. The images that poured from her hand featured repeating motifs of a female figure, always with calm, watchful eyes. The paper was often completely filled — no white space, no resting point.

Gill’s story is often framed through the lens of spiritualism or mental illness. And while those are parts of her history, they don’t fully explain the clarity or control of her work. Her drawings weren’t chaotic; they were meticulous. Quiet. Focused.

She rarely exhibited them. She never sold them. That refusal — whether intentional or circumstantial — places her outside the usual systems. But it also makes her work feel especially personal. Not outsider art as genre, but as position: outside commerce, outside convention, and entirely her own.

Madge Gill

Madge Gill’s artistic output is often described as “channeled” — but it didn’t come with the theatricality you might expect from that word. She wasn’t performing trance states for an audience. She worked quietly, obsessively, filling postcard-sized scraps and enormous rolls of fabric with dense, intricate designs, often while speaking little about what she was doing.

At the center of her practice was “Myrninerest,” the spirit guide she named but never clearly defined. The name itself sounds like a contraction: My Inner Rest. Some have speculated that Myrninerest was less a separate entity and more a manifestation of Gill’s own need for survival, for an inner sanctuary after profound grief and societal alienation.

Her relationship to Myrninerest wasn’t theatrical — it was intimate. A private collaboration between herself and something unseen, whether spiritual or psychological. It gave her permission to create endlessly, without the burden of explaining herself to others.

Rather than making art for fame or money, Gill created an entire internal universe, visible only through the windows she drew. No grand manifestos. No exhibitions in her lifetime. Just thousands upon thousands of marks, stitched together through paper, ink, and will.

In this way, Gill’s work offers something rare: a body of art that isn’t about audience at all. It’s about connection — to the self, to the unknown, and to the act of making itself.

Madge Gill (1882–1961) lived almost her entire life on the margins. Born in East London, she spent much of her youth shuffled between foster homes after being placed in the Barnardo’s care system — a childhood marked by instability and separation. As an adult, Gill endured a series of devastating personal losses: the death of her beloved son, the stillbirth of a daughter, and serious illness that left her partially blind in one eye.

It was after these tragedies that her art exploded into being. Starting in her mid-30s, Gill produced thousands of drawings, most featuring ethereal, otherworldly female figures. She worked primarily in ink on postcards, scraps of paper, and massive rolls of fabric — some of her larger works stretching over 30 feet. Almost none of this was exhibited publicly during her lifetime. She rarely sold her art, believing that it belonged to Myrninerest, the spirit she credited with guiding her hand.

Gill’s life was not glamorous. It was quiet, domestic, often isolated. And yet, through sheer persistence and private necessity, she built an artistic world that rivals anything in the sanctioned galleries of her era. Without a formal audience, without fame, and without the permission of the traditional art world — she made her mark anyway.

Madge Gill’s work fits squarely within the tradition of outsider art — a term often used (sometimes too casually) to describe artists who operate beyond the recognized systems of galleries, critics, and commercial success. But Gill wasn’t “outside” because she rejected fame; she was outside because she created for reasons deeper than recognition. Her drawings were acts of communion, of survival, of personal mythology.

In a world that often equated women’s creativity with frivolity, Gill’s commitment to her visions was radical. She didn’t ask for permission. She didn’t seek validation. She made art because it filled a space that nothing else could. In doing so, she joined a lineage of women whose artistic voices were dismissed, hidden, or misunderstood — not because they lacked skill, but because they dared to create without catering to the systems built to ignore them.

Gill’s work reminds us that art doesn’t have to be loud to be revolutionary. Sometimes the most defiant act is creating quietly, insistently, for yourself alone. In an era obsessed with public validation, her vast, private, spiritual archive feels almost like an act of rebellion: a world built not for consumption, but for connection — even if that connection was between artist and spirit, artist and self.

Gill’s work — obsessive, private, tenderly chaotic — stands in stark contrast to the smooth simulations of AI art. Machine learning scrapes the visible world; Gill created an invisible one. She didn’t optimize for clarity or trend. She didn’t render an aesthetic algorithm. She listened inward, stitched together a labyrinth of lines that even she sometimes couldn’t fully explain. Where AI generates by prediction, Gill created by intuition. Where AI seeks patterns to please, Gill followed visions no one else could see. Her drawings aren’t just images — they are living documents of what it means to be human, fragile, haunted, and fiercely alive.

Prompt+Original

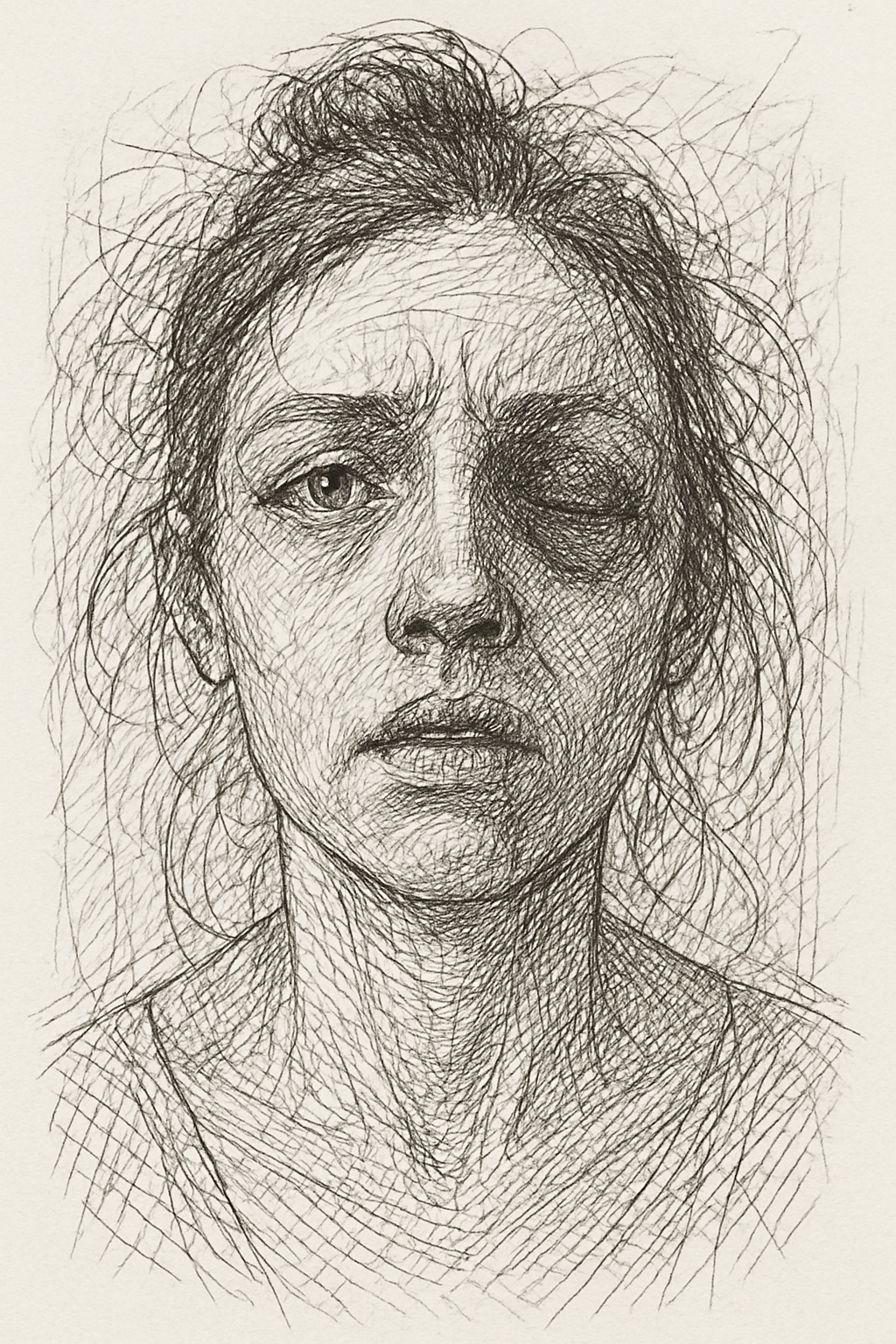

A rough pencil sketch of a sorrowful woman, her hair loosely tied and wildly scribbled at the top of her head. One eye is open, wide and expressive, while the other is swollen shut, darkened with heavy shading. Her mouth is slightly parted with visible tension, a scar etched along her lip. The lines are chaotic and overlapping, giving the portrait a raw, emotional intensity. Her expression suggests pain, resilience, and silent defiance.”

Edit 1+1.2 +1.3

Fine Line ink drawing

Edit 2

Folk art

Feed the Paws…

💜 Help keep the chaos caffeinated and the cats in biscuits.🐈⬛

Every crumb helps. Whether you’re funding feline existential monologues, glitchy portals, or late-night creativity spirals, your support feeds the moglets (and occasionally, the magic).

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Thank you, fellow wanderer.

Your generosity has been noted in the Book of Kindness, which the cats may or may not use as a pillow.

Your light just lit a lantern in Underland.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyDiscover more from River and Celia Underland

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.